4 Minutes Read

After Hours can be considered as an invaluable pedagogical tool for understanding the works of Franz Kafka

Even for the dedicated followers of the acclaimed filmmaker Martin Scorsese, the movie After Hours (1985) is not usually counted among Scorsese’s masterpieces. Paraphrasing the title of Raymond Queneau’s celebrated novel, Scorsese called After Hours “an exercise completely in style.” Perhaps what Scorsese didn’t reveal was his indebtedness to Kafka’s writings which can be read as a transposition of Kafka’s nightmarish world (called by the eponymous adjective Kafkaesque) on the screen. The movie transports the paranoid nightmare of Joseph K from Prague to the city-streets of New York. In terms of its character portrayal, depiction of the milieu, female characters and the treatment of reality, the film is a consistent rendering of the Kafkaesque world. People revolve in a chaotic world, unable to control their own life and After Hours brings this chaos on the screen through the nightmarish and bizarre experiences of Paul Hackett. After Hours can be considered as an invaluable pedagogical tool for understanding the works of Franz Kafka.

The uncanny women characters in After Hours who unsettle the male protagonist Paul Hackett resemble the female characters in the works of Franz Kafka, particularly in The Trail and The Castle. The character of Marcy in the film closely resembles the character of Fräulein Bürstner of Kafka’s unfinished novel The Trial (1925); both the characters enamour the male protagonists but remain elusive from them, leaving them longing and perplexed. Both the characters, so to speak, play pat-ball with the hearts of the male protagonist, and thereby, greatly adds mystery to the inscrutable situations they find themselves in. On his way, in the downpour, the completely wet protagonist Paul visits a bar where he encounters the goofy waitress named Julie, who soon becomes attracted to him. In fact, a major Kafkaesque element in the movie is that almost all the characters misunderstand other characters, which impels them to follow up on impulsive and misguided intentions resulting in perfectly absurd scenarios. When Paul leaves Marcy after a heated-up conversation, she commits suicide. Similarly, Julie was expecting Paul to be intimate with her, perhaps make love to her, but Paul spurns Julie’s advances. Later Julie, out of resentment, seeks vendetta by falsely implicating Paul in the string of burglaries; she sticks posters around the city that portray him as the burglar which, in turn, misguides the city-dwellers to confront and attack Paul.

All these solicitous female characters have an aggressive sexuality, perhaps with a touch of the dominatrix, which is another feature of the Kafkaesque

The female characters in the film initially volunteer to help Paul; like Joseph K, Paul turns to them in his desperation. As Joseph K observes, “I seem to recruit women helpers.” Paul comes to meet Marcy in order to get the paper weights. Later the waitress, Julie, invites Paul to her apartment to give him company and then he encounters the ice-cream vender who insists him to dress his bleeding hand. All these solicitous female characters have an aggressive sexuality, perhaps with a touch of the dominatrix, which is another feature of the Kafkaesque. It is ultimately an entrapping or castrating form of sexuality as symbolized by the pencil sketch of a shark’s sharp teeth enclosing on a penis on the washroom wall of the bar and by the rat-traps surrounding the waitress’ bed. All these women are abject, for one reason or the other, either chained as in the case of Kiki, the sculptress, who was in bondage without explanation or is abandoned like Marcy or like Julie is insecure and expecting betrayal by each and every man. All of them seem to be the sisters of Kafka’s women; women like Leni in The Trail, who eats Joseph K “into the very hairs of his head.”

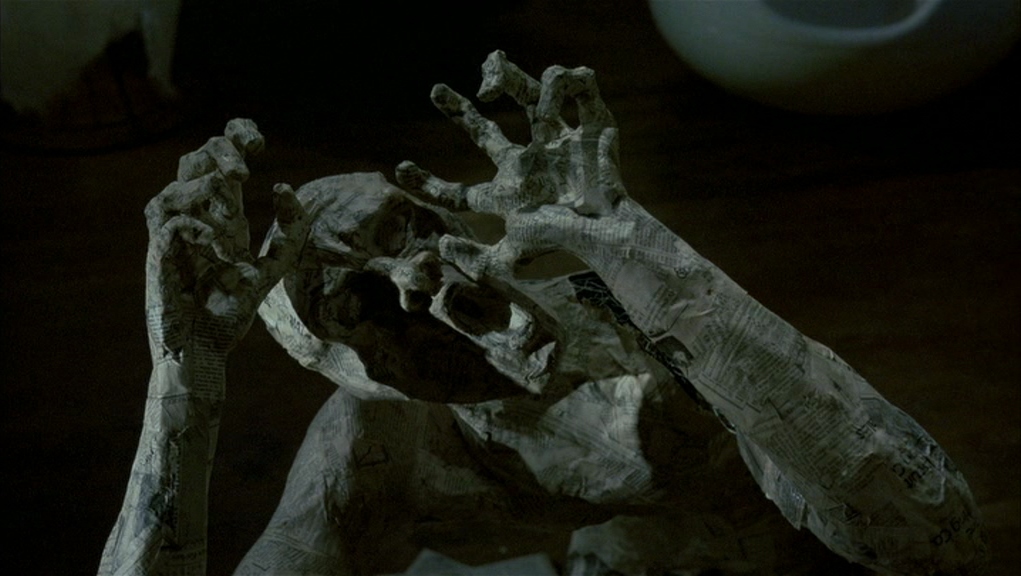

As in Kafka’s novels the female characters who promise aid end by further entangling Paul Hackett in his downward spiral in the movie. The waitress turns against him and her portrayal of Paul as “wanted criminal” through pasting copies of his picture lead the marauding mob to follow him. The character Catherine, the ice cream vendor, leads the vigilant squad against him, who comes to quick conclusions when she sees the poster. And the last female character, the woman in the club, hides him from his pursuers but does so by entrapping him by applying Plaster of Paris on his body and then deserting him.

Despite the obvious comic façade, watching After Hours becomes a disquieting experience, so is reading Kafka. In the film, the language is often the means of miscommunication than the means of communication; appearances always deceive, the rational and objective world breaks down into a series of subjective mental states. The entire Kafkaesque narrative of After Hours is a cumulative effect of misguided intentions and misunderstandings: the narrative of the movie is a cobweb in which all the characters weave simultaneously, to enmesh Paul, who represents the angst-ridden modern individual.

👏👏👏👏👏well written

Can we find kafka’s women characters in any other films of Scorsese, than the mentioned ones in the writing?

Great work Rahul..👏🏻😎

Brilliant work…!!! As always..☺️

A wonderful piece of literary brilliance. The analogies drawn btw the film and kafka’s novels deserves a special applause.Keep writing!

Your Narration is awesome , we expect more and more from you.You can.

Akhildev.P

Head Dept Tourism

KVVS COLLEGE

Great work rahul