6 Minutes Read

Most viewers watching Bong Joon-ho’s classic Memories of Murder for the first time would think of it as a standard crime thriller movie about catching a serial killer. Though the movie is a textbook police procedural, at the hands of the masterful Bong Joon-ho, it becomes a political critique on the law and order bureaucracy. Perhaps Memories of Murder is one of the few movies that can qualify as both detective fiction and political critique. Although Memories of Murder is usually compared to David Fincher’s Zodiac, both movies are totally different in scope and outlook. While both movies essentially focus on the hunt for the serial killer on the loose, Memories of Murder throws limelight on the South Korean society during the 1980’s when the country was under the military dictatorship of General Chun Doo-Hwan.

Memories of Murder is based on the Hwaseong serial killings, which was a killing spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered at Hwaseong, which is about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. The killings began in 1986 and continued for a span of five years, and it shook the nation as it was the first instance of serial killings in South Korean history. Thirty three years after the first body was found, news broke in 2019 that modern DNA testing had identified and linked one man to several victims. The culprit was Lee Chun-jae, fifty-six, a Hwaseong native already in jail for the 1994 crime of raping and murdering his sister-in-law. Lee eventually confessed to all the killings, plus five others, as well as committing thirty rapes. Lee had settled in Hwaseong in 1986 after completing his mandatory military service and he had lived within two miles of most of the committed murders.

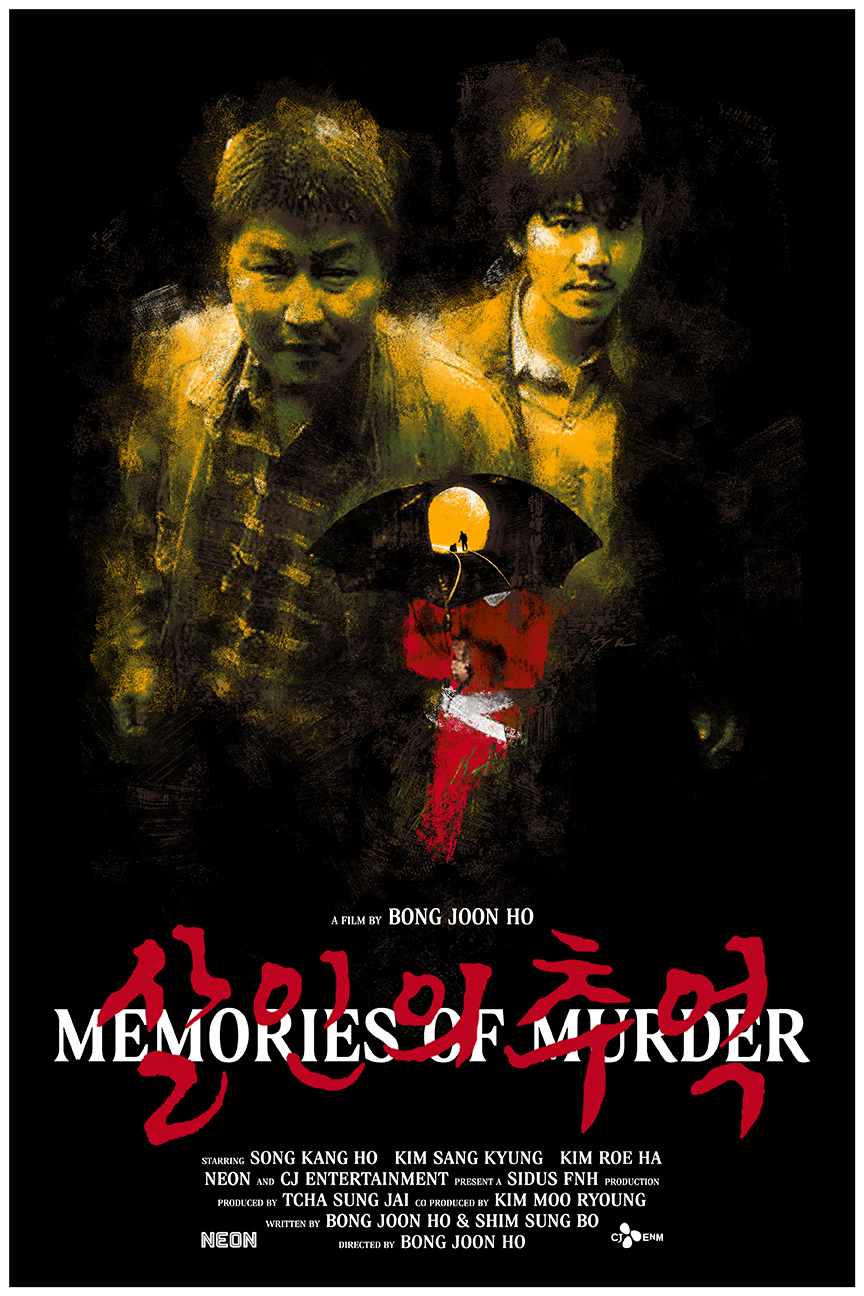

The movie begins with a tranquil sunny afternoon in a rural South-Korean village replete with golden paddy fields. The picture of a quiet country town about to be unsettled by a string of brutal murders. In the movie, we are firstly introduced to two detectives: detective Park Doo-Man (Song Kang-ho) and detective Cho Young-Koo (Kim Roi-ha). Instead of following any standard operating procedure for solving the crime, the duo resort to their idiosyncratic methods. Detective Park Doo-Man believes that he can solve crimes by following his instincts and that his “eyes can read people.” All Detective Park Doo-Man needs is one close glance at the suspect, and he can determine if they are guilty or not. Detective Cho Young-Koo, on the other hand, inflicts brutal violence on suspects to extract a full confession. Detective Cho Young-Koo also wears military boots throughout the movie so that he can inflict more pain than from using his bare fists. All suspects in the movie are brutally tortured by the duo without any fear of repercussions. In fact, the South Korean police was considered to be a weapon at the hands of the military dictatorship so that they could turn dissenters into criminals, or even worse, North Korean spies. The brutality and ineptitude of the detectives is shown in the movie by employing pitch black humor.

The police establishment in the movie is portrayed as being so absurdly inefficient that there is no one to stop the crime scene from ruination. The crime scene of the first murder is ruined by children as they play with the garments of the victim and the crime scene of the second murder is ruined by a group of reporters, kids, and random onlookers. An important piece of evidence in the second crime scene – a shoe print possibly of the suspect – is destroyed minutes after it is found as a tractor runs over it. Seeing the movie, the viewer is forced to think that the primary investigation happens in the boiler room at the basement of the police station, which is used as an interrogation room where the suspects are tortured, far away from the gaze of the public.

The movie also criticizes the callousness of the police in dealing with public protests. A particular scene in the movie shows Detective Cho Young-Koo dragging a female protester by her clothes and kicking her in the face with his military boots. Civilian protests calling for the restoration of full democracy were often ruthlessly suppressed by the authoritarian regime of Gen. Chun Doo-Hwan resulting in hundreds of civilian deaths. In the movie, when the Chief detective requests two garrisons of policemen in an attempt to prevent a murder from taking place at night, he is told that none of them are available as they all went to suppress a demonstration in Suwon city. The movie sheds light on the misallocation of police resources by engaging them to stifle civil protests rather than utilizing them to catch the killer and save precious lives.

A forbidding refrain in the movie is the repeated instance of total blackouts ordered by the government at night to carry out civil defense drills, where people are asked to go inside, close the doors, and turn off the lights. Civil defense drills are carried out to prepare the populace for emergency situations, especially war, where people have to evacuate their homes and find shelter underground. Lights have to be shut out and people have to stay in their underground spaces, which also stops the detectives from doing their work at night. The last murder in the movie, that of a teenage school girl, takes place during the civil defense drill when the town becomes completely still. One feels immense rage at the law and order machinery that fails to protect the life of an innocent teenage girl but painstakingly carries out a defense drill that is totally unnecessary. The movie shows how under a military dictatorship an unusual event like a defense drill becomes a part and parcel of civilian life. Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder is therefore not just a spectacular crime thriller movie with many twists and turns, but also a political critique of the military dictatorship of General Chun Doo-Hwan, seen by many as a dark chapter in South Korean history.