5 Minutes Read

Weeks ahead of Onam this year, around the same time Arundhati Roy’s ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’ hit the bookstores, another collection of articles by some of Malayalam’s best known writers on their mothers also came out as part of Mathrubhumi weekly’s Onam special issue. Most of these articles, as expected, painted a sanitised, idealised picture of mothers. Arundhati’s portrayal of her mother, Mrs. Roy (as she addresses her often), is a world away from this. ‘Warts and all’ would be an understatement to describe the image that she paints.

“I left my mother not because I didn’t love her, but in order to be able to continue to love her,” she writes quite early on in the book, as a reason for her leaving home at 16 to make it on her own in the big, unfamiliar city of Delhi. The things that the kids, especially Arundhati’s brother, had to endure from their mother borders on the unbelievable, not to forget the plight of a dog that meets a terrible end. Roy writes about abuses which made her ‘swirl like water down a sink and disappear’. Though the book is packaged as non-fiction, it at times makes one wish it were fiction, although the narrative flourish is certainly that of fiction.

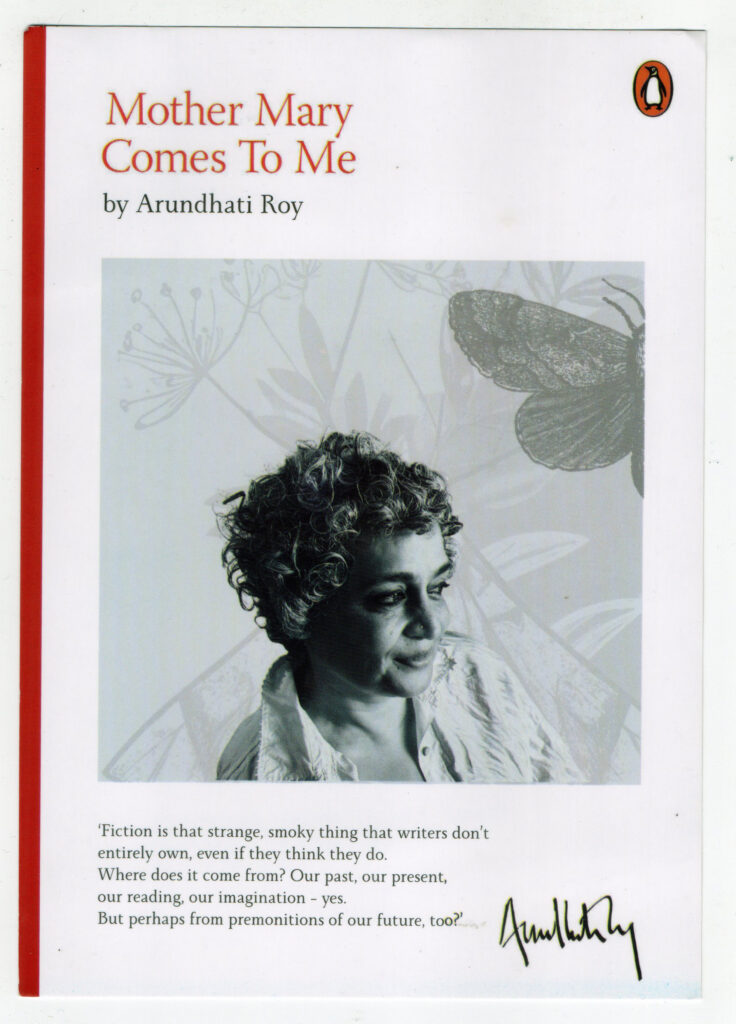

Yet, absent from her recollections is much rancour towards her mother, which might have probably been present had she written this at a younger age. These recollections, coming soon after her mother’s death, are also from the viewpoint of a woman who also had to face trials and tribulations all through her rather privileged life, only because she chose not to rest on her privileges. In a twisted way, it appears that Mary Roy even unknowingly equipped her daughter for her life and the fight ahead, and Arundhati seems to be acutely aware of this fact, when she writes “Mrs. Roy taught me how to think, then raged against my thoughts. She taught me to be free and raged against my freedom. She taught me to write and resented the author I became”, capturing the forever conflicting thoughts about her mother.

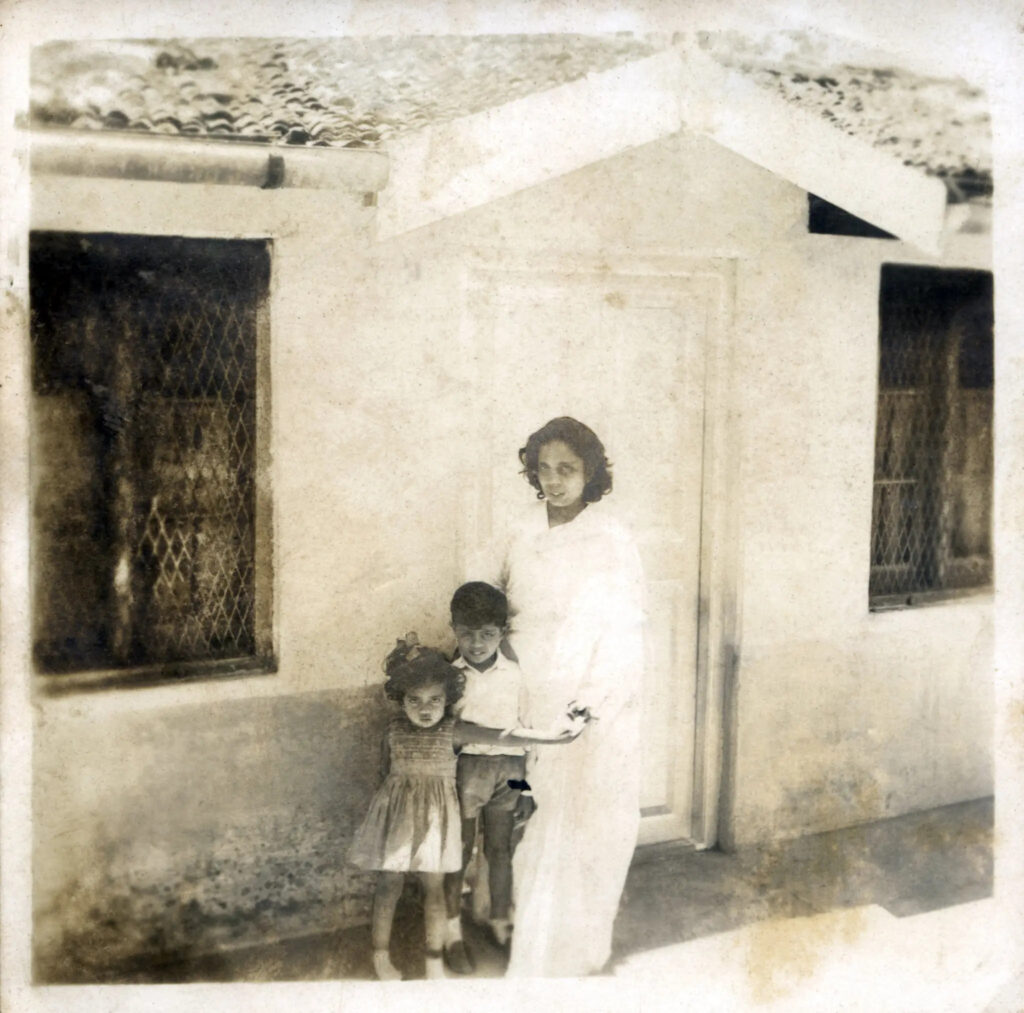

But, elsewhere, she also writes “I would probably understand a lot more about the world and certainly about my country, in which so many people seem to revere their persecutors and appear grateful to be subjugated and told what to do, what to wear, what to eat and how to think.” Succinct personal and political commentary at the same time. In a patriarchal land like Kottayam, where Mrs. Roy set out to build an unconventional school in the 1960s, only someone as commanding and crazy as her could have managed to do what she did. This was someone who back in the day attempted to and succeeded in bringing a sense of equality between the boys and girls, to erode the sense of entitlement of the boys, while giving wings and instilling an undying spirit in the girls.

Amid all these remembrances of things past, there is humour flowing freely in the unlikeliest of places.

The writer also drops more than a hint of how her mother became what she became, with her recounting of the time when Mrs. Roy and her young kids were thrown out from her mother’s house in Ooty, because daughters didn’t have rights over the property, much before she equipped herself to fight the case related to Travancore Christian Succession Act against her brother G. Isaac. Amid all these remembrances of things past, there is humour flowing freely in the unlikeliest of places. The image of Mrs. Roy that emerges from all these recollections is one that provokes anger and commands admiration in equal measure.

‘Mother Mary’ is also at the same time the story of the changes wrought in the writer’s life, especially after dropping her name Susanna and her ‘deliberate transformation into somebody else’. Much needed context is provided to the writing of her books and especially her essays such as ‘The End of Imagination’ on nuclear policy and ‘Walking with Comrades’ on the maoist struggle. She could have rested easily on her Booker glory, but she chose not to, by attaching herself to unpopular, but important causes and living the “restless, unruly life as a seditious, traitor- writer”. She appears to be in the middle of a not so hopeful phase during the four years she took to pen The God of Small Things, but the fanciful stories that follow from the elite echelons, of the manuscript from a debutant writer getting recommended by the who’s who of literature to each other. also tells us that the right connections do matter. But, the royalties from the book and the eventual Booker win did help fund grassroot-level activism.

After the not so impressive The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, an unwieldy book into which she tried to cram all those things that she was concerned with, we are again in Roy’s strong territory in ‘Mother Mary’, which is more in the spirit of the God of Small Things. One only wishes she had also set the record straight on the false claim about Kerala’s first CM EMS Namboodiripad in her first book, since she takes the time to discuss the controversy.